Twists and Turns: A World Cup Fitness Coach Explains Pregame Warm-Ups

nytimes.com

Sarah Lyall – from the New York Times

6–8 minutes

In the final hour before a game, teams’ activities can look as random as recess at the local elementary school. But there is order in the chaos.

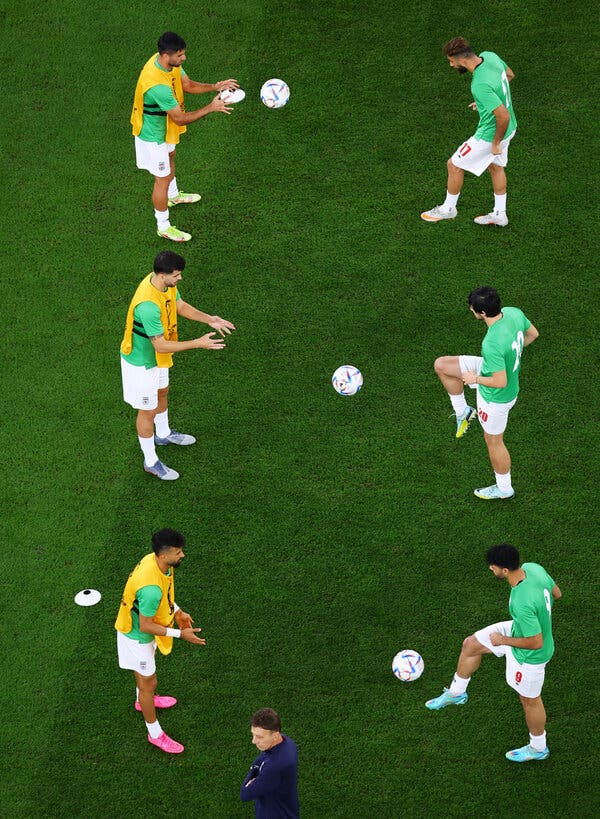

DOHA, Qatar — Watching players perform their pregame warm-ups on the field is one of the more delightful World Cup rituals. They’re skipping, they’re lunging, they’re sashaying. They’re stretching and sprinting. Some are running drills or rocketing balls at goals (or goalkeepers). Others are playing what looks like backyard keep-away, firing one-touch passes around a small circle as two players in the middle dodge and dart to try to win the ball.

It can look as random as recess at the local elementary school (albeit if the kids were professional athletes), but there is organization in the chaos.

To help us understand what is going on, we turned to Andrew Clark, the high-performance coordinator for Australia’s team, known as the Socceroos. (Currently No. 38 in the FIFA rankings, the team exceeded expectations by placing second in Group D; it will play Argentina on Saturday in the first knockout round.)

Clark talked us through the importance of finding the sweet spot between too little and too much pregame preparation, and how to keep the players’ nerves from shredding before the match.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

What is the goal of the warm-up?

The purpose of a warm-up is to prepare the players to perform in the most efficient way, to get them 100 percent ready physically and mentally for the match. There’s a whole lot of detail underneath that of raising body temperature, turning on decision-making and performing the sort of actions that are going to be required in a game. But we have to make sure that we don’t overdo it. We don’t want to overload the players and take away energy that’s needed for the match.

Why can’t you just do the exercises out of sight, inside the stadium?

You want to give the players a sense of what they’re about to walk into. Little things like the wind, the temperature, how wet the grass is, what it feels like, the speed of the pitch. Where are the shadows on the field? Also, just being there and feeling the atmosphere in the stadium gives them energy and takes away a bit of their anxiety.

All the players — the starting lineup as well as the substitutes — are out there, but they’re doing different things.

We’ve got 26 players, but only 11 players can play, plus five players off the bench. For the players on the bench, we’re trying to make sure they’re ready in case they’re called at short notice during the match. But they’re warming up 50 minutes before kickoff, and it might be nearly two hours before they enter the field. What we need is basically just to make sure their systems are starting to turn on, their core temperature is up, their spine is activated.

And then those players will go off and do something more relaxed, like the little circle groups that you see. If you push them too hard, they can go over the top, and you can actually kill their performance. So it’s very important that we keep them calm and relaxed.

In a tournament situation, it’s a constant struggle to try to expose the players who aren’t playing in the matches to enough training. All of them have put in all the work to get to this point. And emotionally it’s difficult. They’re not getting the same gratification as the guy who scores the winner. We work really hard to make sure that we don’t neglect them, that we give them the best opportunity when the time comes.

What about the starting players?

They’re going through a process of turning their body on and slowly working through the dynamic ranges of motion that they’ll be required to perform in the match. Then they’ll do some maximum-velocity type activities.

And then we go into a game-based situation where it becomes spatial and decision making. Usually it’s some sort of position game — 5 versus 5, plus one spare player, or 4 versus 4, plus 3. We want to make sure they’re starting to make decisions similar to what they’re doing in the game.

What about when they seem to be all doing different things?

After that, you start to see things that are specific to certain players. Some players are finishing on goal, some players are crossing. We have our own ideas, but we take guidance from what a player needs in those last few minutes. We know what a central defender needs; we know what a midfielder needs, and we design activities that allow them to do that.

The last thing we do is come together and do something as explosive as possible just to finish off. It’s called post-activation potentiation, or PAP, and it involves an excitation of the neuromuscular system. They walk into the changing room fully activated, fully charged and ready to start the game.

What do they do back in the locker room, after the warm-up but before the game begins?

There’s still 15 minutes to the match, so the challenge for a player is filling that 15-minute gap. It’s a chance to refuel, it’s a chance to go through some final checks, put their pads on, say a few words.

What if they’re super-nervous — or not nervous enough?

Once we’re spread out on the field, the stadium swallows up communication, so this is the time everyone can talk. You have to understand how they’re feeling, whether they need a rocket or whether, OK, there’s a lot of anxiety in this group, we need to be very calm. They can be either overstimulated or under-stimulated, and we try to balance that out, to get back to the midpoint where people are nice and stable and ready to perform their best.

There’s less pressure on you than on teams from places like Argentina and Brazil. Does that make it any easier?

Because of the weight of expectation placed on them, other teams can be overly anxious about needing to beat us. We see that as an opportunity. We prey on their anxiety.

Sarah Lyall is a writer at large, working for a variety of desks including Sports, Culture, Media and International. Previously she was a correspondent in the London bureau, and a reporter for the Culture and Metro desks. @sarahlyall

Subscribe to The New York Times.